FDA Medication Take-Back: Safe Disposal and Why It Matters

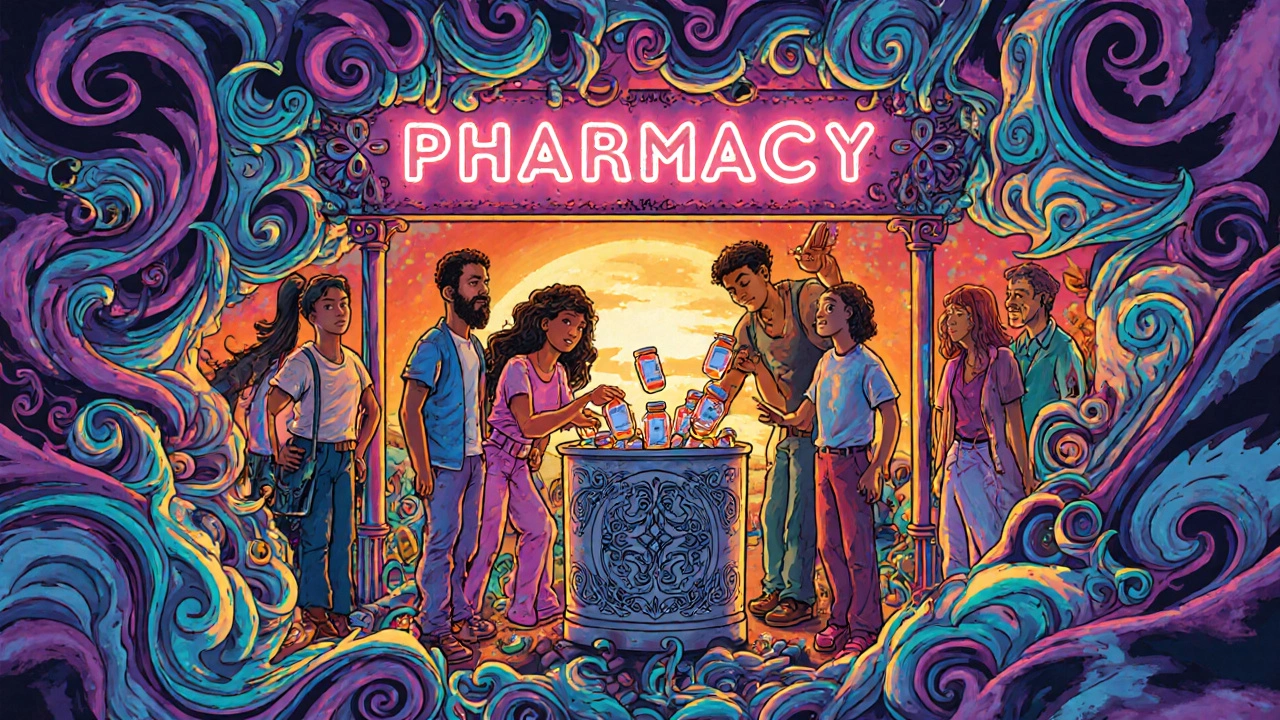

When you have unused or expired medicines sitting in your bathroom cabinet, you’re not just storing pills—you’re holding onto a potential hazard. The FDA medication take-back, a national program that collects unused pharmaceuticals for safe disposal. Also known as drug take-back programs, it’s the only safe way to get rid of pills that could harm kids, pets, or the environment if flushed or tossed in the trash. These programs exist because improper disposal isn’t just careless—it’s dangerous. Every year, millions of pounds of unused medications end up in landfills, rivers, and toilets, contaminating drinking water and fueling addiction. The FDA doesn’t just recommend take-back; it runs and supports the only system proven to stop this.

Take-back bins aren’t just for opioids or painkillers. They accept antidepressants, antibiotics, blood pressure meds, even over-the-counter pain relievers. You don’t need a prescription receipt. You don’t need to remove pills from their original bottles—though keeping them labeled helps. Many pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations have drop-off boxes you can use year-round. Some communities hold annual events, but you shouldn’t wait. If you’re unsure where to go, the DEA’s website (not linked here) lists active locations, and most local pharmacies know the answer. What you shouldn’t do: flush anything unless the label says to. That’s rare. What you shouldn’t do: crush pills or mix them with coffee grounds and toss them in the trash. Those tricks don’t work. Only take-back programs ensure drugs are incinerated safely, without leaking into soil or water.

The pharmaceutical waste, the leftover medication that enters the environment through improper disposal isn’t just an ecological issue—it’s a public health crisis. Studies show traces of antidepressants, hormones, and antibiotics in water supplies across the U.S. Fish are changing behavior. Microbial resistance is growing. And teens are pulling old pills from family medicine cabinets, often with deadly results. The take-back programs, organized efforts to collect and destroy unused medications through secure channels directly reduce these risks. They also cut down on accidental poisonings in children and prevent theft of controlled substances. This isn’t about guilt—it’s about simple, smart action. If you’ve got a bottle of pills you won’t use, don’t wait for a special event. Find a drop box. Do it now.

Every pill you drop off is one less chance for harm. These programs are free, quiet, and easy. No judgment. No questions. Just a bin and a way out. And when you use them, you’re not just protecting your family—you’re helping protect the air, water, and communities around you. Below, you’ll find real stories and practical guides from people who’ve dealt with expired meds, risky interactions, and the quiet danger of keeping pills too long. These aren’t theoretical warnings. They’re lived experiences. And they all point to the same simple truth: if you don’t need it, get rid of it the right way.

Learn the FDA's safe disposal methods for expired medications, including take-back locations, mail-back programs, and when flushing is allowed. Avoid risks to health and the environment with clear, step-by-step guidelines.