Every year, zoonotic diseases jump from animals to humans and sicken millions. You might not realize it, but the bacteria in your pet turtle, the ticks on your dog, or the undercooked chicken on your plate could be carrying something dangerous. These aren’t rare outliers-they’re a constant, quiet threat. About 60% of all known infectious diseases in people come from animals. And 75% of new diseases we’ve seen in the last 20 years started in wildlife or livestock.

What Exactly Are Zoonotic Diseases?

Zoonotic diseases, or zoonoses, are infections that spread between animals and people. They’re caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, or fungi. Some are mild-a rash from a cat scratch. Others are deadly-rabies, Ebola, or plague. The term comes from the Greek word zoon, meaning animal. It’s not just about pets. It’s about wild animals, farm animals, insects, and even the environment they live in.Some of the most common ones include:

- Rabies: A virus spread through bites from infected dogs, bats, or raccoons. Once symptoms show, it’s almost always fatal.

- Salmonella: Found in reptiles, poultry, and eggs. Causes severe diarrhea, fever, and stomach cramps.

- Lyme disease: Carried by ticks that feed on deer and mice. Leads to joint pain, fatigue, and neurological issues if untreated.

- Toxoplasmosis: Spread by cat feces. Dangerous for pregnant women and people with weak immune systems.

- Psittacosis: From birds like parrots. Causes pneumonia-like symptoms.

- Brucellosis: From unpasteurized milk or undercooked meat from infected cows or goats.

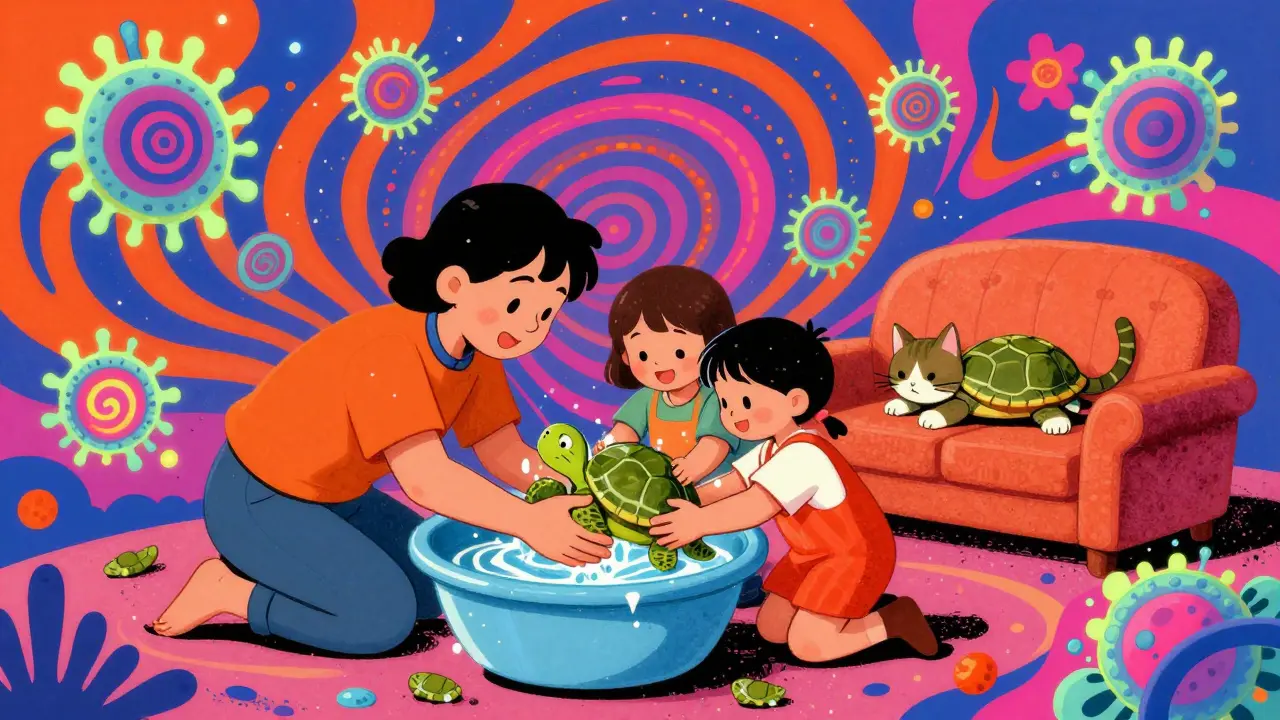

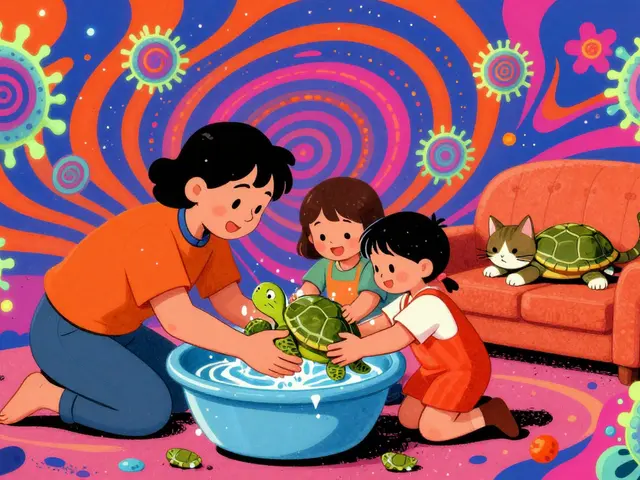

These aren’t just third-world problems. In the U.S., the CDC reports that 1 in 6 people get sick from contaminated food each year-and many of those cases are zoonotic. A family in Wisconsin got salmonella from their pet turtle. A poultry farmer in Minnesota ended up hospitalized for weeks after catching psittacosis from his flock. These aren’t hypotheticals. They happen every day.

How Do These Diseases Jump From Animals to People?

There are five main ways zoonotic diseases make the leap:- Direct contact: Touching, petting, or being bitten by an infected animal. A dog bite can transmit rabies. A cat scratch can give you cat scratch disease.

- Indirect contact: Touching something an animal has contaminated-like a cage, bedding, or soil. Reptile owners often get salmonella this way after cleaning tanks or handling decor.

- Vector-borne: Bites from ticks, mosquitoes, or fleas. Lyme disease and West Nile virus spread this way. Ticks pick up bacteria from mice and then bite you.

- Foodborne: Eating undercooked meat, raw eggs, or unpasteurized milk. Salmonella, E. coli, and brucellosis often come from food.

- Waterborne: Drinking or swimming in water contaminated with animal waste. Giardia is a common parasite found in lakes and streams near livestock areas.

Here’s the thing: you don’t need to be in a jungle to be at risk. Even your backyard can be a hotspot. A raccoon in your garden, a mosquito near your pool, or a pet that licks your face after sniffing a dead mouse-all can be vectors.

Why Are Zoonotic Diseases So Hard to Control?

Unlike diseases that spread only between people-like the flu or COVID-zoonotic diseases require a dual approach. You can’t just vaccinate humans. You have to manage animal populations, monitor wildlife, regulate farms, and protect ecosystems. That’s why the One Health approach exists. It’s the idea that human health, animal health, and environmental health are all connected.But here’s the problem: most countries don’t have systems that connect these areas. Only 17% of nations have fully integrated One Health programs. In the U.S., only 28 states require doctors and vets to report all zoonotic cases. That means outbreaks can go unnoticed until it’s too late.

Take the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Experts later said if they’d tracked sick bats or primates earlier, they might have stopped the spread before it reached human villages. In India’s Nipah virus outbreaks, delays in testing animals led to 17 human deaths from just 23 cases.

Another challenge? Antibiotic resistance. About 20% of antibiotic-resistant infections in the U.S. come from zoonotic sources. Overuse of antibiotics in livestock makes these bugs harder to treat in humans.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Some people are more vulnerable than others:- Veterinarians: 8 times more likely to be exposed than the average person.

- Farmers and slaughterhouse workers: 5.2 cases per 1,000 workers annually.

- Pet owners: 23% have had exposure, most commonly to ringworm or cat scratch disease.

- Children under 5: More likely to put hands in mouths after touching animals.

- Pregnant women: At risk for toxoplasmosis from cat litter or undercooked meat.

- People with weakened immune systems: From cancer treatment, HIV, or organ transplants.

A 2022 survey found that 67% of pet owners didn’t know how to prevent zoonotic diseases before they got sick. That’s not ignorance-it’s a gap in public education.

How to Protect Yourself and Your Family

The good news? Most zoonotic diseases are preventable. Here’s what actually works:- Wash your hands. Always. After handling animals, cleaning litter boxes, or touching soil. Use soap and water for at least 20 seconds. Studies show this cuts transmission by 90%.

- Cook meat properly. Poultry to 165°F, ground beef to 160°F, pork to 145°F. Use a meat thermometer. Don’t guess.

- Avoid contact with wild animals. Don’t feed raccoons, handle bats, or adopt baby deer. They carry diseases you can’t see.

- Use flea and tick prevention on pets. Check them after walks in tall grass or wooded areas.

- Don’t let reptiles in kitchens. Turtles, lizards, and snakes carry salmonella. Keep them away from food prep areas.

- Get pets vaccinated. Rabies shots for dogs and cats are required in most places for a reason.

- Wear gloves when cleaning animal waste. A 2021 study showed this reduces infection risk by 85%.

- Don’t drink untreated water. If you’re camping or hiking, boil or filter water-even if it looks clean.

One of the most overlooked steps? Educating kids. Schools rarely teach children how to safely interact with animals. A child who kisses a puppy after it’s been rolling in dirt doesn’t know they’re risking salmonella. That’s preventable with simple rules: no face-licking, wash hands after petting, and never touch wild animals.

What’s Being Done-And What’s Not

There’s progress. The WHO, FAO, and OIE launched a $150 million global plan in 2022 to build One Health systems in 100 countries by 2026. The CDC just announced $25 million for university centers to train doctors and vets together. In Uganda, dog vaccination campaigns cut human rabies cases by 92%.But the funding is still tiny compared to the cost of outbreaks. A single pandemic can cost over $100 billion. The World Bank says investing $10 billion a year in One Health could prevent 70% of future pandemics-and return $100 for every dollar spent.

Meanwhile, climate change is making things worse. Warmer temperatures are expanding tick habitats. Lyme disease is spreading north in the U.S. and Canada. By 2050, nearly half of North America could be at higher risk.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to be a scientist or a policymaker to help. Start with these steps:- Ask your vet about zoonotic risks for your pets.

- Teach your kids basic hygiene around animals.

- Support farmers who use responsible practices-no antibiotics unless needed.

- Report sick or dead wildlife to local health departments.

- Don’t buy exotic pets. The illegal wildlife trade is a major driver of new zoonotic diseases.

Zoonotic diseases aren’t going away. But they’re not inevitable. Every time you wash your hands after playing with your dog, every time you cook meat to the right temperature, every time you choose a pet from a responsible breeder-you’re helping to stop the next outbreak.

Can you get sick from your pet cat or dog?

Yes. Common zoonotic diseases from pets include ringworm (a fungal infection), cat scratch disease (from scratches or bites), and salmonella (from reptiles or birds). Even healthy-looking pets can carry germs. Always wash your hands after petting, cleaning litter boxes, or handling waste. Avoid letting pets lick your face or open wounds.

Is rabies still a real threat in the U.S.?

Absolutely. While human cases are rare thanks to pet vaccinations, rabies is still common in wild animals like bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes. If you’re bitten or scratched by a wild animal-or even a stray dog or cat-you need medical care immediately. Rabies is almost always fatal once symptoms appear. Post-exposure treatment works if given fast.

Can you get Lyme disease from your dog?

Not directly. You can’t catch Lyme disease from your dog’s bite or saliva. But your dog can bring ticks into your home. Those ticks can then bite you. Check your dog for ticks after walks, especially in wooded or grassy areas. Use tick prevention products and remove ticks promptly with tweezers.

Are backyard chickens safe?

They can be, but they carry salmonella and E. coli. Always wash your hands after handling chickens or collecting eggs. Don’t let chicks or chickens inside your house, especially near food prep areas. Clean coops regularly and keep them away from vegetable gardens. Children under 5 should avoid handling live poultry.

What should you do if you think you’ve been exposed?

Watch for symptoms like fever, diarrhea, vomiting, rash, or swollen lymph nodes within days to weeks after contact. If you’ve been bitten, scratched, or handled an animal and feel unwell, contact your doctor immediately. Tell them about the animal exposure-many doctors aren’t trained to recognize zoonotic diseases. Don’t wait. Early treatment saves lives.

Is it safe to feed wild birds in my yard?

Feeding birds is generally low-risk, but avoid touching dead birds or cleaning feeders without gloves. Bird droppings can carry salmonella and other pathogens. Clean feeders regularly with a 10% bleach solution. Don’t let birds feed near pet food or children’s play areas. If you notice sick or dead birds, report them to your local wildlife agency.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Fear-It’s About Awareness

Zoonotic diseases aren’t the result of animals being “dirty.” They’re the result of how we live-how we clear forests, how we farm, how we treat pets, how we ignore the links between human and animal health. The next pandemic won’t come from a lab. It’ll come from a bat in a forest, a rat in a market, or a tick on your dog’s fur.Knowing how these diseases spread isn’t about paranoia. It’s about empowerment. Simple habits-handwashing, cooking meat right, vaccinating pets, avoiding wild animals-can stop outbreaks before they start. The science is clear. The tools exist. What’s missing is the collective will to use them.

Been a vet tech for 12 years and let me tell you - most people have no idea how many germs their pets carry. I had a client last month who let their bearded dragon sleep on the couch and then ate breakfast right after petting it. No handwashing. No questions asked. Salmonella? Yep. They were in the ER for three days. It’s not scary if you’re smart. It’s stupid if you’re lazy.

Wash your hands. Don’t kiss your reptile. Keep chickens out of the kitchen. Simple stuff. But nobody does it until they’re sick.

The real tragedy isn’t the diseases themselves - it’s how we treat the systems that could prevent them. We pour billions into human medicine while ignoring the ecological and agricultural roots of zoonoses. We vaccinate dogs but not bats. We test meat but not soil. We treat symptoms but not causes.

This isn’t about fear. It’s about humility. We are not separate from nature. We are a node in a web. When the web frays, we feel it first - not because we’re weak, but because we refused to see the threads.

My grandma used to say, ‘If it licks your face, wash your face.’ She didn’t know about salmonella or toxoplasmosis - she just knew animals are dirty sometimes. And she was right.

Just wash your hands after petting stuff. Don’t let your dog lick your sandwich. Keep your turtle out of the sink. Done. No need for a PhD.

Oh wow, another ‘wash your hands’ public service announcement. Next they’ll tell us breathing is risky if there’s a dog nearby. Look, I get it - germs exist. But you know what’s way more dangerous? People who think they can ‘prevent pandemics’ by not letting their cat sleep on the bed.

Meanwhile, the real problem - factory farms, deforestation, wildlife trafficking - gets zero attention. We’re scrubbing our hands while the house burns down. Congrats, we’re all doing our part.

From a One Health perspective, the structural failure isn’t individual behavior - it’s institutional siloing. Human health, veterinary medicine, and environmental monitoring operate in disconnected data ecosystems. The CDC tracks human cases. USDA monitors livestock. USGS tracks wildlife. But there’s no unified surveillance protocol for cross-species spillover events.

Without interoperable data platforms and mandatory reporting across jurisdictions, we’re flying blind. The 2014 Ebola response proved this. We detected human cases - not the bat reservoir. That’s not negligence. That’s systemic design failure.

My buddy got Lyme from his dog’s fur. Not from the dog biting him - from a tick that hopped off and got him while he was mowing the lawn. We thought we were safe ‘cause we had a house dog. Nope. Ticks don’t care. Now we got Frontline on everything, even the guinea pig. And yeah, we wash our hands after petting. No big deal. Just don’t be dumb.

Also - if you’re pregnant, just stay away from kitty litter. Seriously. It’s not worth the risk. I’m not scared, I’m just smart.

USA has the best vets, the best labs, the best science - and still people get sick from pet turtles?? 🤦♀️ We have the tools. We have the knowledge. But some folks think ‘natural’ means ‘safe’ and that’s why we’re losing. 🇺🇸 We don’t need more warnings - we need enforcement. Ban reptiles in homes with kids. Mandate pet hygiene classes. Make vets give out pamphlets like they do with rabies shots.

Stop letting people be stupid with their pets. It’s not ‘freedom’ - it’s public health negligence.

Let’s be honest - this whole ‘zoonotic disease’ narrative is just a distraction. The real threat isn’t your cat or your chicken - it’s the global bioweapon infrastructure that’s been quietly weaponizing pathogens since the Cold War. You think the CDC is telling you the truth about where these strains come from? Please. They’re funded by the same people who profit from antibiotics, vaccines, and panic.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘One Health’ initiative. It’s a PR stunt. A way to make you feel like you’re doing something while the real players - Big Ag, pharma, the UN - quietly restructure the global food chain under the guise of ‘safety.’

Wash your hands? Sure. But ask yourself: who benefits when you’re afraid of your own pet?

ok but what if all this is just a psyop to make us buy more vaccines and hand sanitizer? i mean, think about it - why do they keep pushing ‘one health’? why not just say ‘stay away from animals’? because they want us to think we’re safe if we wash our hands… but what if the real danger is in the water? the air? the 5g towers? i’ve heard the ticks are genetically modified now. they’re not even ticks anymore. they’re nano-robots from the deep state. and your dog? probably a surveillance drone. i checked my cat’s eyes last night - they flickered blue. like a camera lens. 🤫👁️