When your skin starts flaking, red, itchy patches appear, and your fingers or toes swell up like sausages, it’s not just bad luck. For about 1 in 3 people with psoriasis, this is the beginning of something deeper - psoriatic arthritis. It’s not just a skin problem or a joint problem. It’s both. And it’s your immune system turning against you.

What Exactly Is Psoriatic Arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) happens when the same immune system mistake that causes psoriasis - those thick, scaly plaques on your elbows, knees, or scalp - also starts attacking your joints. It’s not just pain. It’s inflammation that can permanently damage bones and cartilage if left unchecked. About 30% of people with psoriasis will develop PsA. For most, the skin comes first - about 85% of cases show psoriasis years before joint pain. But in 5 to 10% of cases, the joints hurt before the skin ever breaks out. That’s why doctors don’t wait for the rash to appear before testing. If you have joint pain, stiffness, or swelling - especially in your fingers, toes, or lower back - and a family history of psoriasis, you need to get checked.The Telltale Signs: More Than Just a Rash

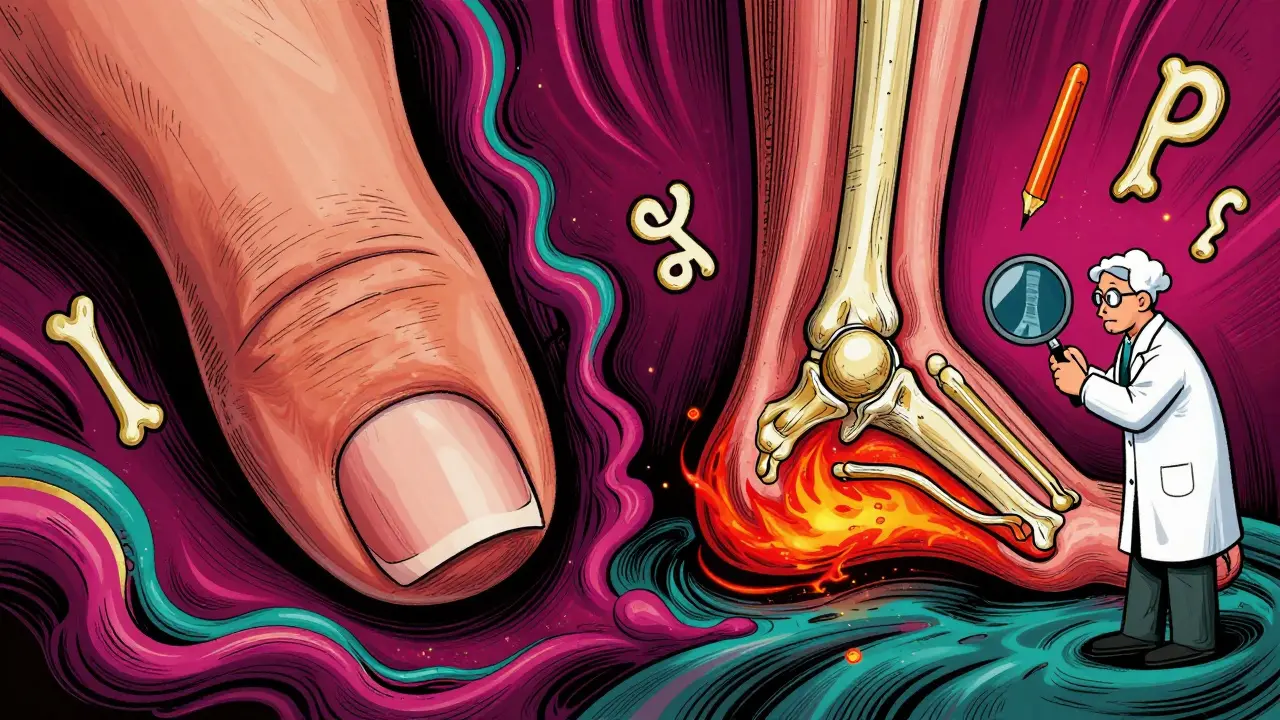

PsA doesn’t look like regular arthritis. It has its own fingerprint.- Dactylitis: One or more fingers or toes swell up completely, looking like little sausages. This happens in about 40% of people with PsA.

- Enthesitis: Pain where tendons or ligaments attach to bone. Think of the back of your heel (Achilles tendon) or the bottom of your foot. It’s not just sore - it’s sharp and worse in the morning.

- Nail changes: Pitting, thickening, or nails lifting off the nail bed. Up to 80% of PsA patients have this. It’s often mistaken for a fungal infection.

- Back and spine pain: If your lower back or neck feels stiff, especially after resting, it could be axial PsA - inflammation in your spine.

- Psoriasis plaques: Red, raised patches with silvery scales. Usually on elbows, knees, scalp, or lower back. But sometimes they’re mild or hidden - under your hair, in your belly fold, or between your buttocks.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for PsA. Doctors use a mix of clues - the CASPAR criteria - a system created in 2006 to make diagnosis more accurate. To get a PsA diagnosis, you need inflammatory joint disease plus at least 3 points from these:- Current psoriasis (3 points)

- History of psoriasis (2 points)

- Nail changes (1 point)

- Negative rheumatoid factor (1 point - rules out rheumatoid arthritis)

- Typical bone changes on X-ray (1 point)

Why This Isn’t Just a Skin or Joint Issue

PsA is a systemic disease. That means it affects your whole body.- Heart disease: People with PsA have a 43% higher risk of heart attack. Inflammation doesn’t just eat away at your joints - it damages your arteries.

- Metabolic syndrome: High blood pressure, belly fat, high cholesterol, and insulin resistance hit 40-50% of PsA patients - twice the rate of the general population.

- Depression and anxiety: Nearly 1 in 3 people with PsA struggle with mood disorders. Chronic pain, visible skin changes, and fatigue take a toll.

- Reduced life expectancy: Studies show PsA patients live 30-50% shorter lives, mostly because of heart problems.

What Treatments Actually Work?

Treatment has changed dramatically in the last 15 years. It’s no longer just “take ibuprofen and hope.”- NSAIDs (like naproxen or celecoxib): Help with mild pain and swelling, but they don’t stop joint damage.

- Methotrexate: A traditional DMARD. Works for some, especially if skin is the main issue. But it’s not strong enough for severe joint or spine involvement.

- Biologics: These are game-changers. They target specific parts of the immune system:

- TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept): Great for joint and spine pain. About 50-60% of patients see a 20% improvement in symptoms.

- IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab): Best for skin and nails. Often clear up plaques completely.

- IL-12/23 inhibitors (ustekinumab): Work well for both skin and joints.

- JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib): Oral pills that block inflammation signals inside cells.

What’s Next? The Future of PsA Care

New drugs are coming fast. By 2027, doctors expect 70% of PsA patients to be on biologics or targeted pills within two years of diagnosis - up from 40% today.- IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab, risankizumab): Already approved for psoriasis, now showing strong results for joints too.

- TYK2 inhibitors (deucravacitinib): First oral drug that targets a specific immune pathway with fewer side effects than older JAK inhibitors.

- Bimekizumab: A dual blocker of IL-17A and IL-17F - shows deeper skin clearance than any other drug in trials.

What You Can Do Today

If you have psoriasis and joint pain:- See a rheumatologist - not just a dermatologist. PsA needs both skin and joint expertise.

- Track your symptoms. Use a notebook or app. Note which joints hurt, when, and how bad.

- Ask about your heart health. Get blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar checked yearly.

- Don’t ignore mood changes. Depression isn’t “just in your head.” It’s part of the disease.

- Stay active. Low-impact exercise like swimming or cycling protects joints and reduces inflammation.

- Quit smoking. It makes PsA worse and increases heart risk.

Can psoriasis turn into psoriatic arthritis?

Not exactly. Psoriasis doesn’t “turn into” psoriatic arthritis. Both are caused by the same underlying autoimmune problem. If you have psoriasis, your immune system is already overactive. In some people, that inflammation spreads to the joints, leading to PsA. About 30% of people with psoriasis develop it - but not everyone does.

Is psoriatic arthritis the same as rheumatoid arthritis?

No. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) attacks the lining of joints symmetrically - both hands, both knees. PsA is more unpredictable. It often affects just one side, causes sausage-like fingers (dactylitis), and is linked to psoriasis and nail changes. RA patients usually test positive for rheumatoid factor; PsA patients don’t. The treatments overlap, but the diagnosis and long-term risks are different.

Can you have psoriatic arthritis without psoriasis?

Yes, but it’s rare - only 5-10% of cases. If you have joint pain and a family history of psoriasis, you might still have PsA even if you’ve never had a rash. Some people get joint symptoms first, and the skin flare comes later - sometimes years later. Doctors will still diagnose PsA if your joint pattern matches and you have other signs like nail pitting or enthesitis.

Does diet affect psoriatic arthritis?

No single diet cures PsA, but what you eat can help. Obesity worsens inflammation and makes medications less effective. Cutting back on sugar, processed foods, and red meat can reduce flare-ups. Some people benefit from anti-inflammatory diets rich in fish, vegetables, nuts, and olive oil. Losing even 5-10% of body weight can improve joint pain and skin symptoms.

Is psoriatic arthritis genetic?

Yes, genetics play a big role. If a parent or sibling has psoriasis or PsA, your risk goes up. Specific genes like HLA-B27, HLA-B38, and HLA-B39 are linked to higher risk. But genes alone don’t cause it. Something - stress, infection, injury, or smoking - triggers the immune system to go wrong. Having the genes just makes you more likely to react that way.

Can psoriatic arthritis be cured?

There’s no cure yet. But with the right treatment, many people reach remission - meaning no active inflammation, no pain, no joint damage. Some stay in remission for years. The key is early diagnosis and sticking with treatment. Stopping meds too soon can lead to flare-ups and permanent damage.

How often should I get checked if I have psoriatic arthritis?

If you’re on treatment, see your rheumatologist every 3-6 months to check your progress. Blood tests, joint exams, and sometimes imaging are needed to see if your meds are working. Even if you feel fine, you still need regular checkups - damage can happen without pain. If your symptoms change or flare up, call your doctor sooner.

Been living with psoriasis for 12 years and just got diagnosed with PsA last year. The sausage fingers were the weirdest thing - thought I’d crushed my toe in my shoe. Turns out, it was my immune system being a jerk.

Now I’m on secukinumab and my skin’s clearer than it’s been since college. Still tired all the time, but at least I can hold a coffee cup without wincing.

Yo, I’m from Nigeria and we don’t talk about this stuff much. My cousin had psoriasis and everyone thought it was contagious. He got joint pain and no one took him to a doctor for two years. He’s on biologics now and it’s changed his life. If you got skin issues and your joints hurt - go get checked. Don’t wait like we did.

THIS. THIS IS THE POST I NEEDED. I thought I was just getting old. My knuckles hurt, my nails looked like they’d been chewed by a raccoon, and I was too embarrassed to show my doctor. Turns out? I’m not broken - my immune system is just mad. Started biologics last month. I cried the first time I put on shorts without hiding my legs. Thank you.

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me I’ve been told for years that my joint pain is ‘just arthritis’ and my skin rash is ‘eczema’… and it’s actually the same thing? And doctors didn’t connect the dots until I begged? That’s not medicine. That’s negligence. I’m not mad, I’m just… disappointed.

It’s fascinating how the immune system can misfire like this - attacking the skin, then the joints, then silently creeping into the arteries. We treat symptoms like they’re separate problems, but it’s all one system screaming for help.

Maybe the real issue isn’t just finding the right drug, but learning to see the body as a whole. Not skin, not joints, not heart - one interconnected network that’s been betrayed.

Early diagnosis is critical. Delayed treatment correlates strongly with irreversible joint damage and increased cardiovascular risk. The CASPAR criteria remain clinically valid and underutilized. Patients should be referred to rheumatology at first sign of dactylitis or enthesitis, regardless of visible psoriasis.

Systemic inflammation demands systemic management.

ok so… i’ve been thinking… like… if your immune system is like, ‘hey i’m gonna attack your skin’… and then it’s like ‘oh wait i forgot my keys’ so it goes and attacks your knees… is that… like… a glitch? or is it… intentional? like… is your body trying to tell you something? maybe you need to meditate more? or eat less dairy? or forgive your ex? i don’t know… i just… feel like… there’s more to it…

also… i think i have psa… i think… maybe… i’m not sure… i didn’t read all of this… but i think… yeah…

Psoriatic arthritis is not the same as osteoarthritis. It is an autoimmune condition. Treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone is insufficient. Disease-modifying therapies, including biologics, are required to prevent structural damage. Regular monitoring by a rheumatologist is essential. Lifestyle modifications including weight management and smoking cessation improve outcomes. Do not delay evaluation.

I’ve been a nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen patients ignore this until they can’t walk. I’ve held hands during joint injections. I’ve watched people cry because they thought they were ‘just getting old.’

You are not alone. You are not lazy. You are not imagining it. Get seen. Get tested. Get help. Your future self will thank you.

My mom had psoriasis and never told anyone. She hid her legs. She never complained about her back. She died at 62 from a heart attack. No one knew she had joint pain. No one knew she was tired all the time. I got diagnosed with PsA last year. I’m not letting history repeat. I’m on treatment. I’m telling everyone. You deserve to be seen. You deserve to feel better. Don’t wait like she did.