Opioid Rotation Dose Calculator

This tool calculates equivalent opioid doses with recommended safety margin. Never adjust doses without medical supervision.

The American Society for Pain Management recommends reducing the new opioid dose by 25-50% when rotating opioids to avoid overdose risk.

Methadone Warning: Methadone has a long half-life and requires special monitoring. Doses may need to be reduced by 50-75% and increased slowly over several days.

When long-term opioid use stops working-or starts causing more harm than relief-doctors sometimes suggest opioid rotation. This isn’t about quitting opioids. It’s about switching from one opioid to another to better control pain while cutting down on side effects like nausea, drowsiness, or confusion. For many patients, this simple change makes a big difference.

Why Switch Opioids at All?

Not all opioids work the same way in every person. What helps one person might make another feel awful. You might be taking morphine and find you’re too sleepy to get out of bed, or you’ve been on oxycodone for months but still can’t sleep because of constant nausea. Or maybe your pain isn’t getting better, even after increasing the dose. That’s when opioid rotation comes in. Research shows that between 50% and 90% of patients who switch opioids see improvements in either pain control or side effects. A 2013 study of 49 cancer patients found that switching from morphine to other opioids like oxycodone or fentanyl led to fewer episodes of vomiting, less sedation, and clearer thinking. The key isn’t just changing the drug-it’s finding one that your body tolerates better.When Is Opioid Rotation Recommended?

Doctors don’t rotate opioids just because they can. There are clear clinical reasons:- Unbearable side effects: Sedation, vomiting, confusion, muscle twitching, or hallucinations that don’t go away even after adjusting the dose.

- Pain isn’t improving: You’ve doubled or tripled your dose, and your pain score hasn’t dropped. This often means your body has hit a wall with that particular opioid.

- Drug interactions: You’re on another medication that interferes with how your body processes the current opioid.

- Route change needed: You can’t swallow pills anymore, so you need an injection, patch, or suppository form.

- Organ function changes: If your kidneys or liver start failing, some opioids become harder to clear from your body, increasing overdose risk.

- Cost or availability: Your insurance no longer covers your current opioid, or it’s out of stock.

Importantly, opioid rotation is not for sudden pain flares. Those need different strategies. It’s also not for people who just don’t like the side effects but aren’t actually suffering from them. The goal is to find a better balance-not to avoid opioids entirely.

The Most Common Swaps and What They Do

Not all opioid switches are equal. Some combinations work better than others for specific problems:- Morphine → Oxycodone: Often reduces nausea and constipation. Many patients report feeling more alert.

- Morphine → Fentanyl (patch or lozenge): Good for patients who can’t take pills. Also reduces vomiting and dizziness.

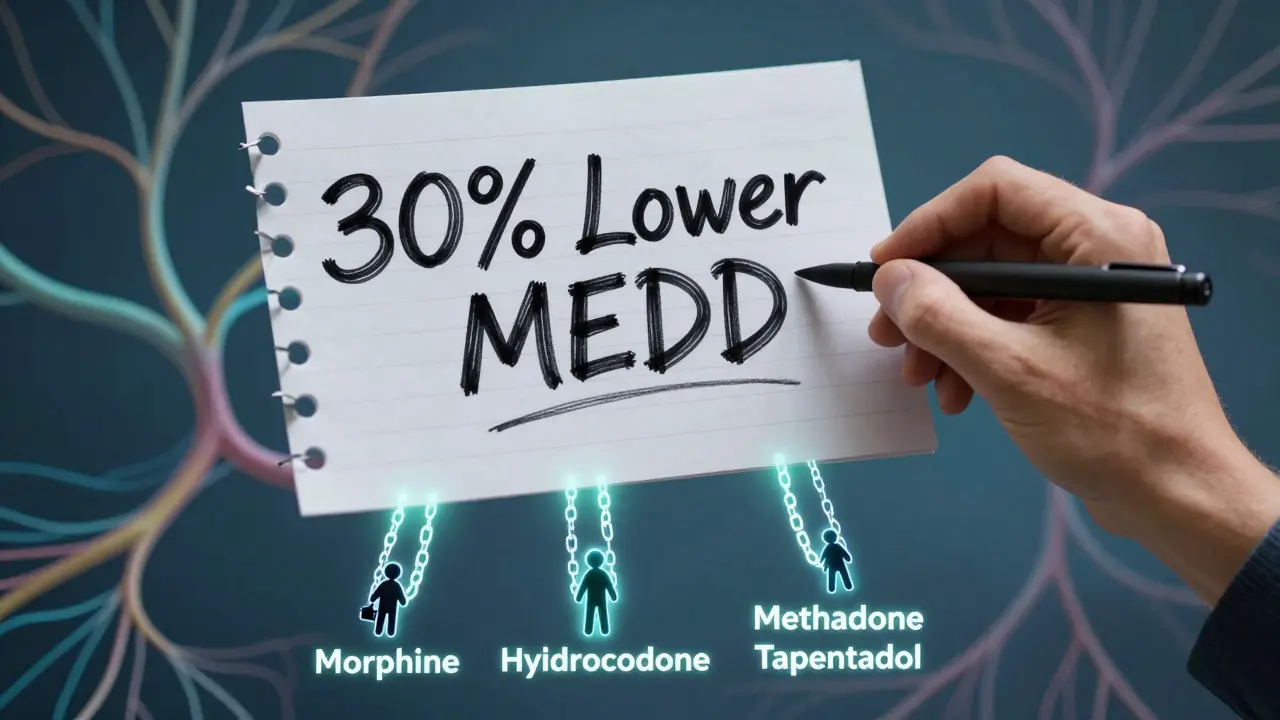

- Hydrocodone → Methadone: Methadone is unique. It often allows doctors to lower the total daily dose while maintaining pain control. This is because methadone lasts longer and works differently in the brain.

- Hydromorphone → Tapentadol: Used when patients have nerve pain along with their usual pain. Tapentadol works on two pathways, not just one.

One surprising finding: switching to methadone doesn’t just help with side effects-it often lowers the total amount of opioid needed. One 2023 study showed methadone reduced the Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD) by an average of 30% in patients who switched from other opioids. That’s huge. Lower doses mean less risk of overdose, less constipation, and fewer respiratory issues.

The Math Behind the Switch: Equianalgesic Dosing

You can’t just swap one opioid for another at the same dose. That’s dangerous. Too much could cause overdose. Too little could leave you in pain. Doctors use something called equianalgesic dosing-basically, a conversion chart that estimates how much of one opioid equals another in pain relief. But these charts aren’t perfect. They’re based on averages. Your body might need 20% more or less than the chart says. For example, the old rule was: 10 mg of morphine equals 1 mg of methadone. But newer data suggests it’s closer to 9:1, especially when switching for side effects. If you’re switching because you’re too sedated, you might need even less methadone-maybe 12:1. Why? Because your body is already overwhelmed. You’re not just replacing a drug-you’re resetting your nervous system. That’s why doctors always reduce the new opioid’s starting dose by 25% to 50%. This is called the “safety margin.” It’s not a mistake. It’s intentional. Your body hasn’t fully adjusted to the new drug yet. You’re still partially tolerant to the old one. Going full dose could be deadly.Methadone: The Exception

Methadone is different. It’s not just another opioid. It has a long half-life, meaning it sticks around in your body longer. It also blocks pain signals in a way other opioids don’t. That’s why it’s so effective for nerve pain and why it often lowers total opioid use. But methadone is tricky. Its effects can build up over days. A dose that feels fine on day one might cause trouble on day three. That’s why switching to methadone requires extra monitoring. Doctors often start with a very low dose and increase slowly over a week or two. In one outpatient palliative care study, methadone was the only opioid that consistently lowered MEDD. All other rotations didn’t reduce total daily doses. That makes methadone a powerful tool-if used carefully.What About Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

This one’s surprising. Sometimes, long-term opioid use makes your body more sensitive to pain. You feel more pain, even though you’re taking more opioids. This isn’t addiction. It’s a biological change in your nerves. It’s called opioid-induced hyperalgesia. It used to be ignored. Now, it’s a major reason to rotate. Patients with this condition often have pain that gets worse with higher doses. They’re stuck in a loop: more pills → more pain → more pills. Switching opioids-especially to methadone or buprenorphine-can break that cycle. Some patients report their pain improves within days of the switch.

Why It’s Not Always a Success

Opioid rotation isn’t magic. About 10% to 50% of patients don’t improve. Why?- Too much reduction: Doctors may cut the dose too far out of fear, leaving the patient in pain.

- Wrong choice: Switching from morphine to hydromorphone might not help if both work the same way in your body.

- Underlying issues: If your pain is from nerve damage, arthritis, or depression, an opioid swap alone won’t fix it.

- No follow-up: If you don’t get checked in a week or two, side effects might creep back.

One study found that patients who had follow-up visits within 14 days after rotation were twice as likely to report improvement. Communication matters.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

If your doctor suggests a switch, don’t just say yes. Ask:- “Why are we switching? Is it for side effects, pain control, or both?”

- “What’s the new dose going to be, and why?”

- “Will I be on a lower dose at first? How much lower?”

- “How will we know if it’s working? What symptoms should I watch for?”

- “When should I come back? What if I feel worse?”

Good doctors will have a plan. If they can’t explain the math behind the switch, get a second opinion.

The Big Picture

Opioid rotation isn’t a new idea. The first formal guidelines came out in 2009, and they’re still the gold standard today. But science is catching up. We now know genetics play a role-some people metabolize opioids faster or slower because of their DNA. Future tests might tell you which opioid your body is likely to handle best. For now, the best approach is simple: monitor closely, reduce doses conservatively, and choose the opioid that matches your specific problem. Nausea? Try fentanyl. Drowsiness? Try oxycodone. Nerve pain? Try methadone. Overdose risk? Lower the total dose.It’s not about finding the “best” opioid. It’s about finding the one that lets you live without being controlled by side effects.

Can I switch opioids on my own if I’m having side effects?

No. Never change your opioid without medical supervision. Even small changes can lead to overdose or withdrawal. Opioid rotation requires careful calculations, monitoring, and follow-up. If you’re having side effects, call your doctor. Don’t adjust your dose or switch pills on your own.

Is opioid rotation the same as tolerance or addiction?

No. Tolerance means your body needs more of the same drug to get the same effect. Addiction is compulsive use despite harm. Opioid rotation is a clinical strategy to improve safety and effectiveness. You might be perfectly compliant with your medication and still benefit from a switch because your body responds differently to different opioids.

How long does it take to know if the new opioid is working?

It varies. For side effects like nausea or drowsiness, you might notice improvement within 2-3 days. For pain control, it can take 5-7 days as the drug builds up in your system. Methadone can take up to two weeks to reach full effect. Your doctor should schedule a follow-up within 7-14 days to check your progress.

What if the new opioid doesn’t work?

You might try another rotation. Some patients need two or three attempts before finding the right match. But if multiple switches fail, your doctor may consider non-opioid options like gabapentin, physical therapy, nerve blocks, or even psychological support for chronic pain. Opioid rotation isn’t the only path.

Does opioid rotation reduce the risk of overdose?

Yes-when done correctly. By lowering the total daily opioid dose (especially with methadone) and avoiding dangerous combinations, rotation can reduce overdose risk. But if the conversion is done incorrectly, the risk increases. That’s why it must be managed by someone experienced in pain medicine.

Switching opioids is way more nuanced than people think. I’ve seen friends go from morphine to methadone and swear it saved their life-but only because their doctor was super careful with the dosing. One wrong step and you’re in the ER.

ok so i just read this whole thing and like… why is no one talking about how methadone is basically a secret weapon?? i had my uncle switch and his medd dropped 40% in 3 weeks. also he stopped puking. i mean. wow. also typo: ‘equianalgesic’ is spelled right but looks like a typo lol

in india we dont even have access to most of these options. morphine is hard to get, fentanyl patches are luxury items. we rely on tramadol and paracetamol combos. rotation? what rotation? if you can even get one opioid, you count your blessings. this post is very usa-centric.

THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING NO ONE TALKS ABOUT-OPIOID-INDUCED HYPERALGESIA. I’M NOT KIDDING. MY MOTHER WAS ON OXYCODONE FOR 8 YEARS, DOSE KEPT GOING UP, PAIN GOT WORSE, SHE THOUGHT SHE WAS ADDICTED-BUT SHE WASN’T. SHE WAS JUST IN MORE PAIN BECAUSE THE DRUG WAS BREAKING HER NERVES. THEN THEY SWITCHED HER TO METHADONE AND SHE CRIED THE FIRST DAY SHE SLEPT WITHOUT PAINKILLERS. IT WASN’T A RELIEF. IT WAS A REBIRTH. WHY ISN’T THIS IN EVERY MED SCHOOL TEXTBOOK?

if you’re taking opioids long term you’re already on a slippery slope. rotation doesn’t fix the problem, it just delays the inevitable. why not just get off them entirely? the real issue is that doctors are too lazy to refer patients to PT or cognitive therapy.

so if methadone reduces total dose by 30%, why isn’t it the first-line rotation? is it because of stigma? or because it’s harder to monitor? curious because this feels like the most logical move.

YESSSSSS this is the info I needed!! I’ve been helping my dad through this and we were so lost. Methadone = game changer. Also, the 25-50% safety margin? That’s genius. I’m printing this out for his next appointment 💪❤️

As a palliative care nurse, I’ve seen this play out 100+ times. The magic isn’t in the drug-it’s in the follow-up. Patients who get a call on day 3 and another on day 7? They’re 3x more likely to stabilize. That’s the real intervention. Also, tapentadol for neuropathic pain? Lifesaver. The dual MOA is underutilized. And yes, the MEDD drop with methadone? It’s real. We track it weekly. No fluff.

so i just read the equianalgesic part and i think… maybe the charts are wrong because they’re based on healthy people? like, if you’re 70, have liver damage, and been on morphine for 12 years, your body doesn’t process drugs like a 25yo athlete. we need personalized conversion tables. like, genetic testing + metabolite analysis. why isn’t this a thing yet? also, typo: ‘equianalgesic’ again lol

you people are so naive. opioids are a trap. no matter how you rotate them, you’re still feeding the addiction machine. this is just the pharmaceutical industry’s way of keeping you dependent longer. they profit from rotation. they profit from follow-ups. they profit from your suffering. wake up.

Let me ask you this: if the body metabolizes opioids differently based on CYP450 polymorphisms-and we now have pharmacogenomic testing available-why are we still using population-based conversion tables from 2009? This isn’t medicine. It’s roulette. And the fact that we don’t screen for UGT2B7 or COMT variants before rotation? That’s not negligence. It’s systemic malpractice. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way. To keep patients dependent. To keep profits high. To keep doctors from having to think.

Neuropathic pain + tapentadol = total game changer. Also, the 25-50% safety margin is non-negotiable. I’ve seen two overdoses from skipping it. Don’t be that person. And yes, methadone’s half-life is wild-30 hours on average but can stretch to 60. That’s why day 3 is the real test.

Thank you for writing this. As someone who’s been on chronic opioids for 15 years, I can say rotation saved my quality of life. I went from morphine to oxycodone and suddenly I could play with my kids again. No more 3 p.m. naps. No more vomiting after every meal. It wasn’t magic. It was science. And it worked because my doctor listened. If you’re scared to ask for a switch-you’re not alone. But you deserve to feel better.